Smartphone users’ data is juicier than desktop users’ data as it contains more detail on the users’ day-to-day activity, ranging from status updates to taking a selfie to geo tagging. Everything is a point of interest for market analysis, even for entities beyond a country’s borders.

With some countries openly accusing foreign apps of espionage, and many others discreetly suspicious of them, the Indian government has asked its military personnel to uninstall a list of Chinese apps. This is not the first time the Indian government has asked its defence community to be wary of Chinese hardware and software. Some of the apps named in the recent list of blacklisted apps are:

- SHAREit

- UC Browser

- Mi Community

- Mi Store

- 360 Security

A look at the geolocation of servers that many of these apps connect to showed the following:

SHAREit (com.lenovo.anyshare.gps) ( MD5: CB2C0A445B571035CE38CEAB91E01EBC )

WeChat (com.tencent.mm) ( MD5: CF237D05AB4782081AC70CBD2210EE3E )

UC Browser (com.UCMobile.intl) ( MD5: CA56AB59D7E6CE87A0B690DBF083487B )

- android.permission.USE_CREDENTIALS

- android.permission.MANAGE_ACCOUNTS

- android.permission.AUTHENTICATE_ACCOUNTS

- android.permission.READ_CONTACTS

- android.permission.GET_ACCOUNTS

- android.permission.ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION

- android.permission.ACCESS_COARSE_LOCATION

When installing an app, users should always carefully go through the list of access permissions requested by the app and should not just mechanically tap the “Accept” button.

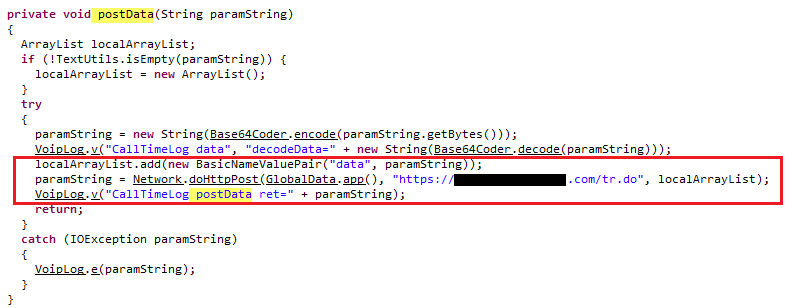

We examined a few of the apps blacklisted by the Indian government to check the kind of information being sent to the parent server. We did not find anything malicious but as seen in the two screenshots below, potentially sensitive information like device-id, build model, android version, etc. are being sent to parent servers located in China. Device-Id, also popularly known as IMEI number, is a common artefact collected by many apps for legitimate purposes. But from a privacy point of view, device-id is a unique and better artefact than IP address to identify an individual device and thereby allowing the tracking an individual user’s habits on the device. This helps marketing agencies to target the individual with tailored ads and certainly helps nations in (psychological) cyberwarfare against each other.

The image below shows one of the apps sending the data to its server.

Figure3: Data being sent to the parent server in china

Today, as users are already getting used to the intrusion on their privacy and beginning to consider it as part of normal modern life, it’s getting difficult to come up with a clear demarcation of what’s good app behaviour and what’s not vis-à-vis PII (i.e. “Personally Identifiable Information”).

However the onus of gauging and enforcing data privacy standards and security should not be placed on the user, buried deep inside some EULA (i.e. “End User License Agreement”) full of legalese in small print which most people wouldn’t understand even if they read it. Instead it must be a moral and legal requisite of the app owners to maintain certain minimum standards enforced by regulatory government bodies. This is one of the prominent issues addressed by the European Union’s GDPR whose imminent implementation should be beneficial to users both in the European Union, and elsewhere by proxy.

Users are advised to always install apps only from the official Google Playstore. But given the scenario today that for any popular app on the Google Playstore there are many fake apps and malicious clones on the Playstore itself, an average user has to be all the more careful in selecting the correct app.

Baran Kumar.S & Sunil

Threat Research Team